Just like today where cycling clubs have their own design of jerseys, in the early days of cycling it was also common for each cycling club to have an official uniform for riding. Unlike today, though, this usually constituted a tailored jacket and breeches, wool stockings, and a cap or even a type of protective helmet.

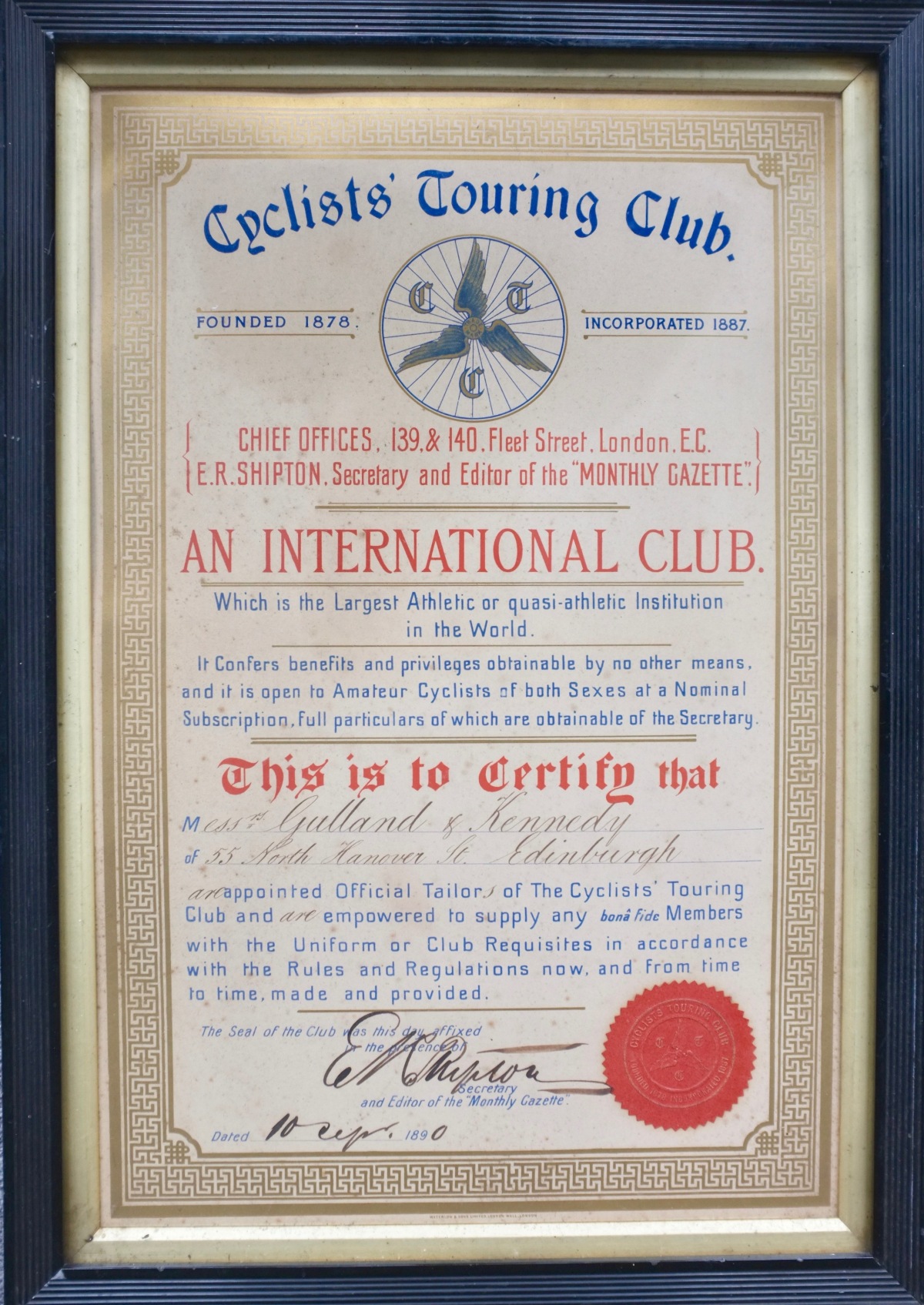

Recently I came across the certificate above, issued in 1890 by the CTC to appoint an official tailor for club uniform. The uniform specifications were laid down by the club in their rules, although the uniform was not compulsory. In the British Library there is a copy of the CTC Uniform Rules and Regulations, which is dated 1888. Remarkably this allows us to see the exact materials specified for the uniform, since there are samples of the actual cloth glued into the publication. Additionally there are details of the uniform requirements for women. The author of the regulations was E.R.Shipton, the Secretary of the CTC, whose flowing signature is on the certificate above.

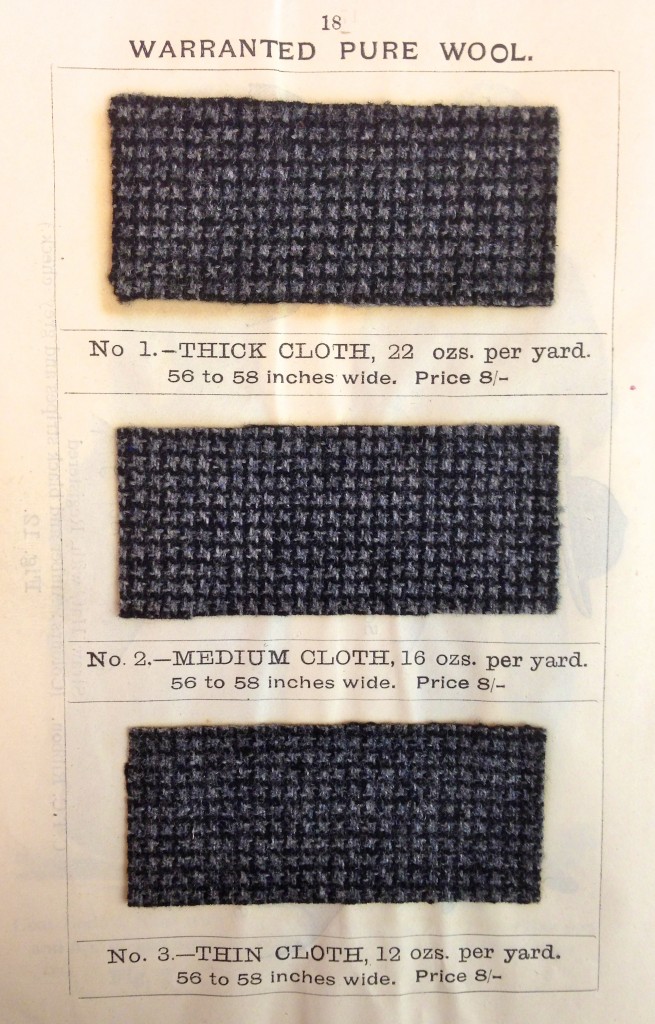

Carton Reid on his excellent blog Roads Were Not Built For Cars writes about this publication and the CTC uniform in detail. Initially the club adopted green serge for their garb, but it was found that ‘it showed every speck of mud or dust’ of which there was plenty on the roads of the time, so it was discontinued in 1882 in favour of grey tweed. This was settled on ‘after many months of patient investigation’ and testing of over forty different cloths. At the time wool was favoured against the skin, as a hygienic and sanitary fabric, far better than cotton for the rigors of riding. Dr.Gustav Jaeger was partly responsible for this, with his ‘Sanitary Woolen System’ which was popularised by the Royal Family, amongst many other patrons. So, woolen undergarments were also specified.

Jackets were either Norfolk or Lounge style, with knee length breeches or knickerbockers, a grey checked flannel shirt, hand knitted socks, and a choice of headgear ranging from a cricket type cap to a helmet. The helmet would probably have been lined with cork, like a pith helmet of the period.

For ladies there was a coat bodice or Norfolk jacket in the same cloth, and a skirt with or without apron or pannier. Knickerbockers were also an option, and would seem to be a little more practical than the skirts pictured below. However, at that time there was still opposition to women wearing such a garment.

Three weights of wool tweed were available:

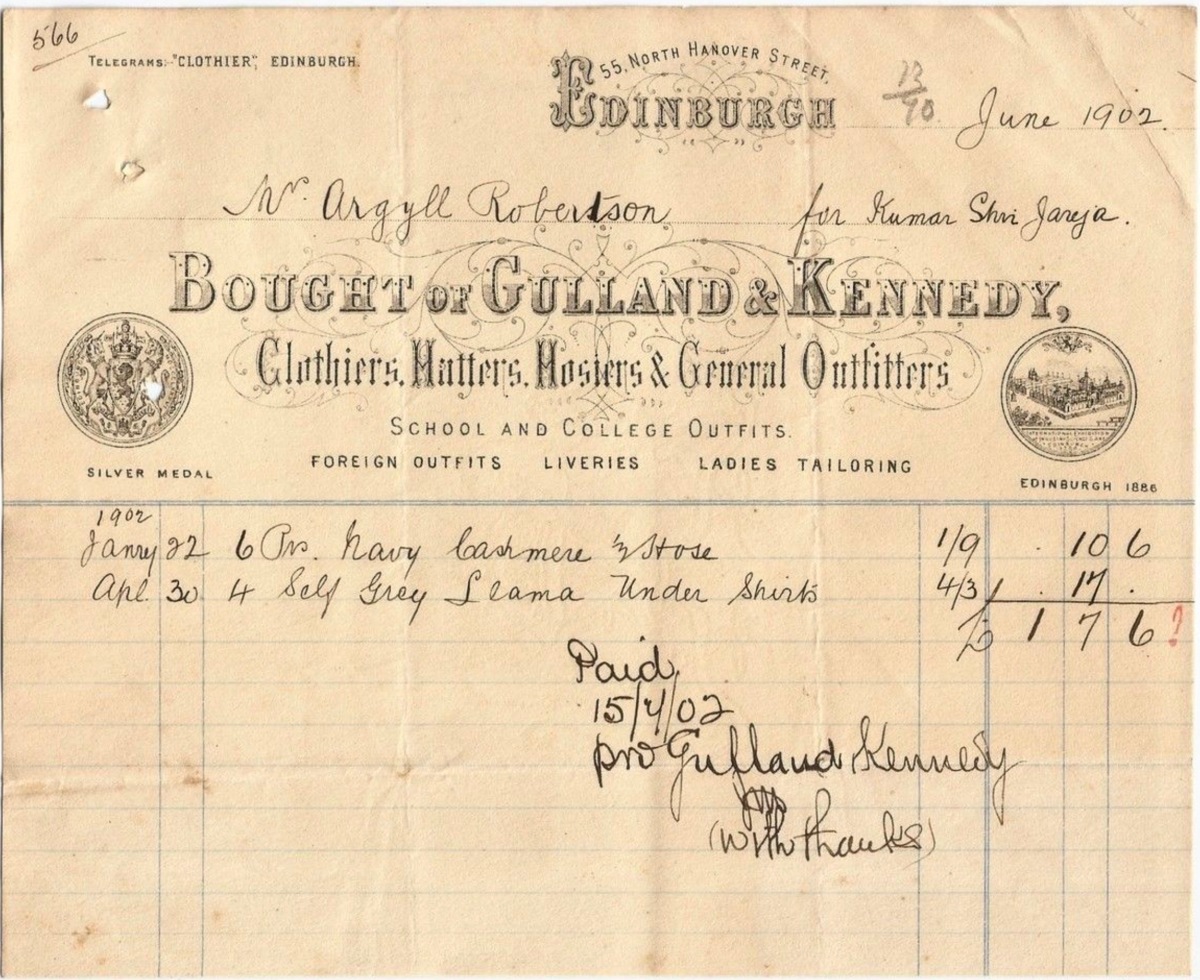

After settling on the regulation uniform, the CTC then appointed official tailors in major cities, so that the quality of the product could be assured. The certificate in question appoints Gulland and Kennedy of Edinburgh as their official supplier. In London one of their appointees was Goy and Co. who made the racing cap in my previous blog post.

Gulland and Kennedy was a well known tailors established in 1886, and the certificate is a very rare survivor of it’s type.

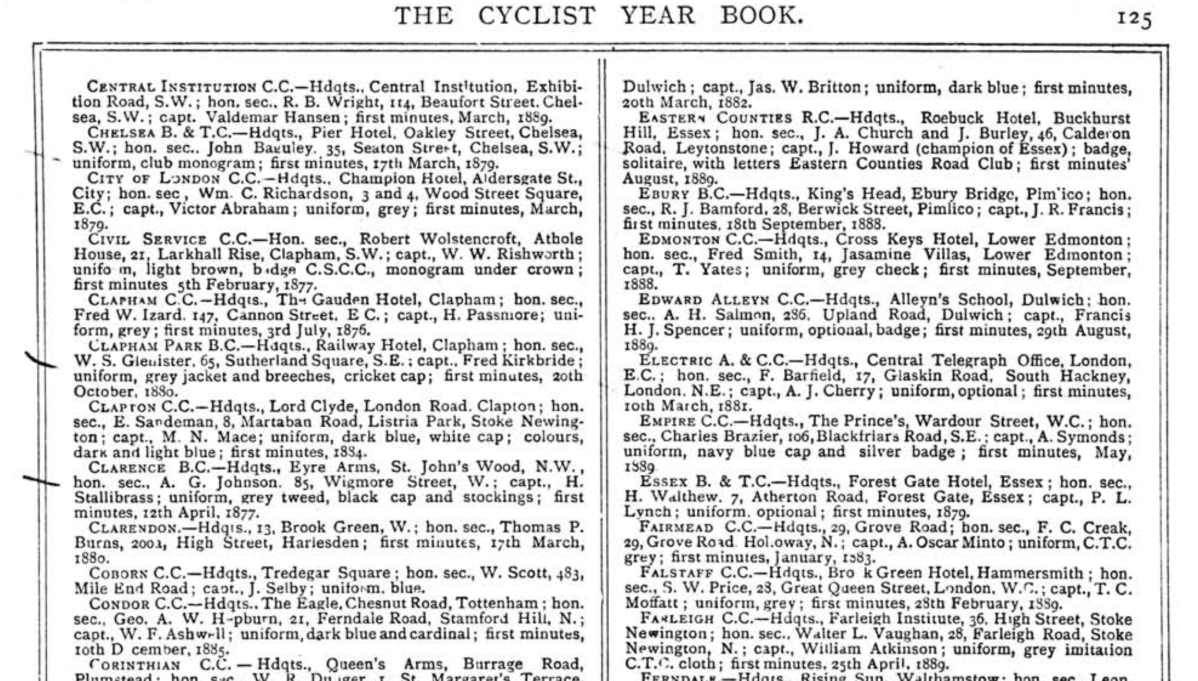

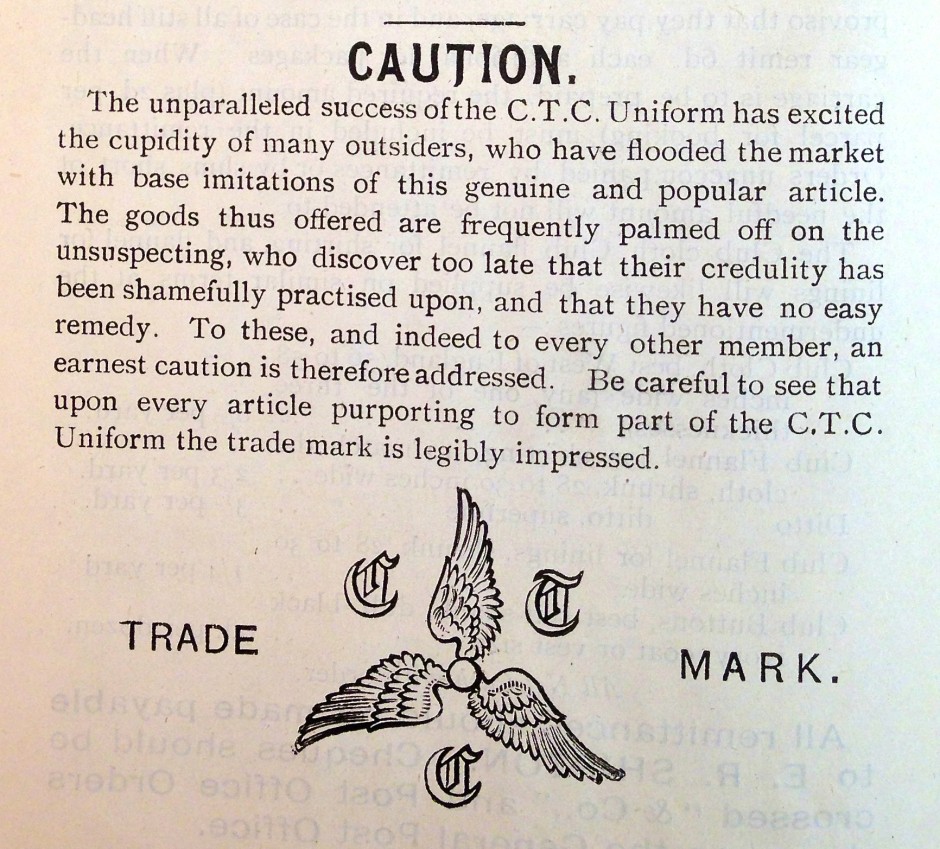

In The Cyclist Christmas Number for 1890 (above) the uniform colours of all recorded clubs are quoted. For instance, Clapton CC of East London, wore dark blue with white cap, whilst Edmonton CC wore grey check. This would generally have been of tweed or wool serge, with different weights of cloth available for summer and winter use… if you were wealthy enough! The Anfield Bicycle Club of Liverpool adopted an all black uniform, leading to them being dubbed ‘The Black Anfielders’. However, a number of clubs took a more casual stance with no uniform specified. Amusingly the Farleigh CC states ‘grey imitation CTC cloth’ for their outfit. The CTC would not have been amused having claimed that their fabric was of unsurpassed quality and warning about the inferiority of imitators:

With thanks to Carlton Reid for the images of the CTC Uniform Rules and Regulations. I can also recommend his excellent book Roads Were Not Built For Cars.

Thanks also to Ray Miller and the Veteran-Cycle Club online library, for The Cyclist Year Book 1890

You must be logged in to post a comment.