The ‘End to End’ record, or Land’s End to John O’Groats, holds a particular fascination in British cycling history. It’s holders have included previous heroes such as the great G.P.Mills, T.A.Edge and Lawrence Fletcher. Until 1903 the records were paced, but from then on they were under the strict rules of the Road Record Association (RRA), which disallowed pacing and laid down the route and other criteria to be followed.

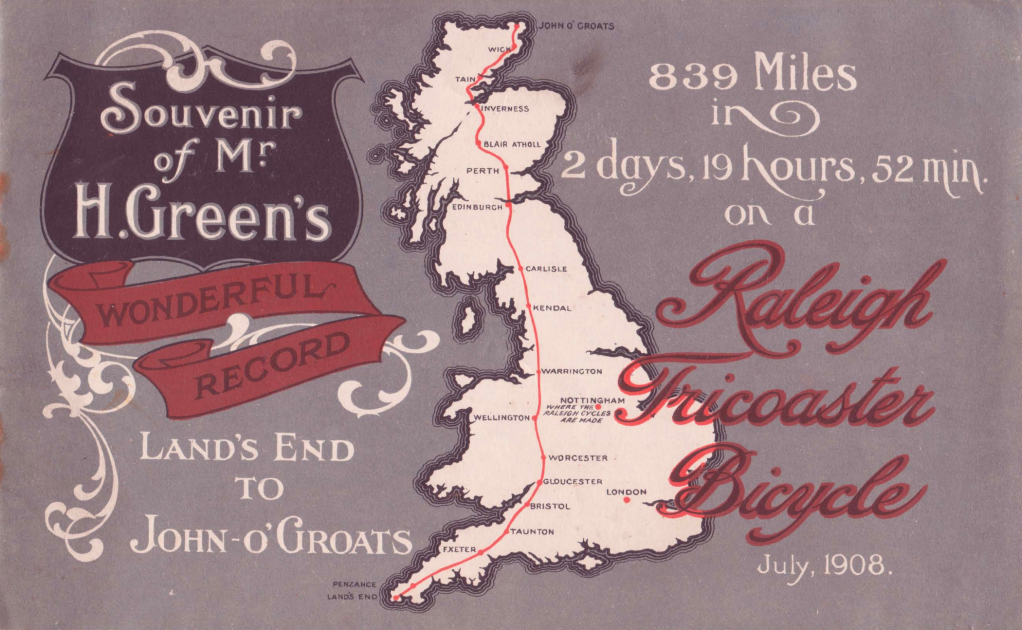

In 1908 H.E.Green set the new record time of 2 days 19 hours and 52 minutes, for 837 1/2 miles, which was to stand for a remarkable 21 years. Green was a predominant time triallist who had held 15 RRA records from 50 miles, through to 12 and 24 hour time trials. Similarly Jack Rossiter was a distinguished performer, holding record in 100 miles, London to York and 12 hours TT. In 1929 he set out to beat Harry Green’s time and take the Blue Riband of solo cycling.

In the intervening period since Green’s ride there had been a rule change. The ride previously included a ferry crossing, which for Rossiter’s ride was bypassed, adding 28 1/2 miles to the distance, making a total of 866 miles.

His mount, provided by Raleigh, was a Club Model built up to his favoured, rather idiosyncratic, specification. It was said to have weighed just 23 1/2 pounds (10.7 kilos) and was fitted with a 3 speed Sturmey-Archer K-series hub gear, with a medium gear of 78 inches. It had a forward curved seat pin, and ‘Marsh’ drop bars set at a downward angle which seemed to be quite popular at that time. The brake levers were unusual, being inverted at the end of the drops. The Brooks saddle was fitted with a Resilion padded cover.

There was just a small forward extension mudguard in front of the steerer to prevent mud splashing into his face. Lighting was provided by a Lucas Acetylene lamp, with only a reflector at the rear. His clothing was the typical outfit of a time triallist, with thin alpaca jacket and alpaca knitted tights. He was said to have made his own waterproof jacket!

Setting out from Land’s End on the 22nd August 1929 at 08.00, the weather was by no means ideal! In rain and with muddy road surfaces, he crashed at Penzance. Picking himself up he was thankfully uninjured and carried on over Bodmin Moor with reduced tyre pressures to give better traction in the wet conditions.

click on an image to open gallery

His route was detailed on this route card, which I acquired for the National Cycle Archive. It is believed to have belonged to Rossiter, the notes being written either by him or a member of his team.

Travelling through Exeter he reached Bristol at 19.00, 50 minutes ahead of schedule, despite the crosswinds and rain. At Gloucester he fitted his lamp and rode on through the dark to Kidderminster and then Whitchurch, where the landlord of the Swan Hotel welcomed him at 02.45 to give him some refreshments. During the night it was damp and cold, and Jack made use of his pullover and cardigan, as well as his waterproof jacket. Onward to Warrington where he took breakfast over the course of a 22 minute stop.

The image above is of the back of the support lorry, showing some of the spare gear, McVitie Digestive Biscuit tin, and his carbide lamps. A carbide container tube is seen just behind the lower lamp. The lamps are the substantial Lucas Calcia King No.326, which stands 7 inches high (17cm). Carbide lamps have a water reservoir above a calcium carbide container. The water is dripped slowly onto the carbide producing acetylene gas, which is lit to produce a very white, bright and effective beam. The support lorry had to keep at least 100 yards behind the rider, so he was entirely reliant on his lamp during the night. I happen to have exactly this type of lamp in my collection, my one dated 1925:

As daylight broke, Rossiter was shaken by the cobbled streets of Wigan but pressed on at speed towards the Lake District. He was 2 hours ahead by the time he reached Kendal. Stops for refreshments were generally very brief, just a matter of a few minutes, but at Kendal he stopped for 1 hour 20 mins, to enjoy a bath, massage and some rest. Onward he pressed over the steep climb of Shap, in a ‘low’ gear of 59 inches (!) gaining on record all the time. Before Carlisle, at 14.00, he changed his rear wheel for one fitted with a Sturmey combination which was slightly lower geared; 55/72/94 instead of 59/78/102. This seemed to make him more comfortable and, coupled with a more favourable wind direction, allowed him to make excellent progress through Gretna, Lanark and Stirling.

Rolling down into Perth in the darkness, he had an unfortunate meeting with a rabbit who ran into his front wheel and brought him down heavily. His knee was badly grazed and both arms bruised, but his bike was unscathed and he continued into the city at 00.53, where his wounds were dressed and treated with Iodine, whilst he took on food.

Sandwiches with cheese, custard, rice, Virol, eggs and coffee were the main constituents of his diet, along with beef tea, Peppermint Creams and McVities Digestive Biscuits. Virol was a popular ‘health food’ which contained malt extract, beef fat, various vitamins, glucose, fructose, egg and orange juice!

In Blair Athol, at 05.45 he stopped for beef tea and digestive biscuits before the long climb over the Grampian Mountains. The weather had cleared, giving him some welcome moonlight, but the wind had changed to a headwind for the ascent. Just after the climb a howling gale came up, which he would have endured whilst climbing had he not been so far ahead of schedule. When the Pentland Firth came into view he knew he was almost at his goal, and when he rode into the forecourt of the John O’Groats Hotel at 21.22, he was greeted by the timekeeper F.T.Bidlake, who announced that he had beaten the record by 6 hours 29 minutes. Rossiter replied: “That’s good, now what about a spot of something to eat?”

On the first day he had covered 392 miles, and the second 307 miles. His average speed was nearly 15 mph. His stops accounted for 4 hours 32 minutes, so he was actually riding for 2 days 8 hours 50 minutes. The record time was 2 days 13 hours 22 minutes for 866 miles, which was to stand for 5 years until beaten by the great Hubert Opperman.

There is a connection between Rossiter and someone else featured on my blog, because he was married to Lilian Morris, the sister of the great frame builder H.R.Morris. I believe the photographs, now in the National Cycle Archive and featured in this post were owned by Rossiter’s family and given to Dick Morris.

Amongst these documents was also a most unique item, a souvenir programme and menu for the celebratory dinner in December 1929, at the Frascati Restaurant on Oxford Street, London. The menu is signed by numerous important figures in the field of cycling. They include the timekeeper for the record, former great racing cyclist and tricyclist, and vice-president of the CTC, F.T.Bidlake, former racing cyclist and president of the CTC Herbert Stancer, and the Chairman of Raleigh, Sir Harold Bowden.

Acknowledgements:

National Cycle Archive (Reg Charity No 272792)

Veteran-Cycle Club Library

You must be logged in to post a comment.